The Hierarchy of Thought: How a New, Brain-Inspired AI Is Learning to Truly Reason

For the past several years, the field of artificial intelligence has been dominated by a single, powerful idea: scale. The prevailing wisdom has been that by building ever-larger language models and training them on ever-larger datasets, we can unlock progressively more sophisticated capabilities, including the holy grail of complex reasoning. Yet, for all their remarkable fluency, these Large Language Models (LLMs) have been running up against a fundamental wall. When faced with problems that require deep, multi-step, algorithmic thinking, they falter. Their apparent reasoning is often a clever illusion, propped up by a technique called Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting.

Now, a groundbreaking new architecture is challenging this entire paradigm. The Hierarchical Reasoning Model (HRM), a compact 27-million-parameter model, is demonstrating that intelligent architecture, not sheer scale, may be the key to unlocking true machine reasoning.[1] Inspired directly by the hierarchical and multi-timescale processing of the human brain, HRM can solve complex logic puzzles and navigate intricate mazes that leave even the largest state-of-the-art LLMs completely stumped. It does so with a tiny fraction of the parameters and training data, suggesting a new path forward for AI—one based on principled design rather than brute force.

This report delves into the architecture, mechanics, and profound implications of the Hierarchical Reasoning Model. It explores why current models have hit a reasoning ceiling, how HRM's brain-inspired design overcomes these limitations, and what its astonishing performance means for the future of artificial general intelligence.

The Reasoning Wall: Why Today's AI Is Hitting a Computational Limit

To understand the significance of HRM, one must first grasp the critical, yet often overlooked, limitations of the models that dominate the AI landscape today. The very term "deep learning" is, in the context of LLM architecture, something of a misnomer.

The Paradox of "Deep" Learning

Despite their name, the core architecture of today's LLMs is paradoxically shallow.[1] A standard Transformer model consists of a fixed number of layers stacked on top of one another. While this number can be large, it is finite. This fixed depth places a hard ceiling on the model's computational power, constraining it to complexity classes such as $AC^0$ or $TC^0$.[1] In practical terms, this means they are mathematically incapable of solving problems that require polynomial time to compute, a category that includes a vast range of algorithmic and planning tasks.[1] They are not, in a formal sense, Turing-complete.

This theoretical limit has very real consequences. Research shows that on tasks requiring extensive search and backtracking, such as solving difficult Sudoku puzzles, simply increasing a Transformer's depth or width yields diminishing returns.[1] Performance on these complex reasoning problems saturates far below optimal levels, even for exceptionally deep models. This evidence strongly suggests that the prevailing "scaling is all you need" paradigm has a fundamental blind spot; you cannot force a shallow architecture to perform deep computation simply by making it bigger.[1]

Chain-of-Thought: The Ingenious Crutch

The AI community developed a clever workaround for this architectural deficiency: Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting.[1] CoT works by externalizing the reasoning process into language. Instead of asking a model to solve a complex problem in one go, the prompt guides it to break the problem down into a series of simple, intermediate steps written out as text. The model then tackles each small step sequentially, using its powerful next-token prediction ability to generate the "reasoning" chain.[1]

While ingenious, CoT is ultimately a crutch, not a solution to the underlying problem.[1] Its prevalence is not a sign of advanced reasoning capabilities but rather a symptom of the model's core inability to maintain and execute a deep computational graph internally. The model isn't truly reasoning; it's performing pattern matching on a pre-digested, linearized sequence of thoughts. This approach is fraught with weaknesses:

- Brittleness: CoT relies on carefully defined, human-like decompositions of a task. A single misstep, a logical error, or even a misordering of the steps can derail the entire process, leading to a completely wrong answer.[1]

- Data Hunger: Teaching a model to follow these linguistic reasoning patterns requires enormous amounts of training data, contributing to the ever-growing data appetite of the LLM ecosystem.[1]

- High Latency: For genuinely complex problems, the chain of thought can become exceptionally long. Generating hundreds or thousands of tokens to solve a single problem is computationally expensive and slow, resulting in high response times.[1]

The field has been trying to force a shallow architecture to perform deep reasoning using linguistic tricks. This has built much of the perceived progress in AI reasoning on a fragile foundation, creating a hard ceiling on capabilities. For AI to take the next step, it needs a new paradigm—a model capable of "latent reasoning," where complex computations are performed efficiently within the model's own internal hidden states, just as they are in the human brain.[1]

A Blueprint from the Brain: Introducing the Hierarchical Reasoning Model (HRM)

The Hierarchical Reasoning Model represents a fundamental shift away from the brute-force scaling of homogenous architectures and toward a more intelligent, principled design inspired by the most powerful reasoning engine known: the human brain.[1] Rather than treating intelligence as a monolithic capability that emerges from a single, uniform network, HRM's design posits that it is an emergent property of specialized computational modules collaborating across different timescales.

Three Pillars of Neural Computation

The architecture of HRM is grounded in three well-established principles of neural computation observed in neuroscience [1]:

- Hierarchical Processing: The brain is organized hierarchically. Lower-level sensory areas process immediate, detailed information, while higher-order cortical areas integrate this information over longer periods to form abstract plans and representations.[1]

- Temporal Separation: These different hierarchical levels operate at distinct intrinsic timescales. This is reflected in neural rhythms, such as slow theta waves (4-8 Hz) associated with planning and memory, and fast gamma waves (30-100 Hz) associated with local computation. This temporal separation allows slow, high-level guidance to stably direct rapid, low-level execution.[1]

- Recurrent Connectivity: The brain features extensive recurrent connections, or feedback loops. These loops allow for the iterative refinement of internal representations, enabling deep, coherent chains of thought without the prohibitive computational costs that have plagued artificial recurrent networks.[1]

The Two Minds of HRM: High-Level and Low-Level Modules

Based on these principles, HRM is constructed with two interdependent recurrent modules that function as a cohesive system [1]:

- The High-Level (H) Module: This module acts as the "strategist" or "planner." It operates slowly, updating only once per computational cycle. Its role is to handle abstract, deliberate reasoning, integrating the results of the low-level computations to set the overall goal for the next phase of problem-solving.

- The Low-Level (L) Module: This module is the "tactician" or "executor." It operates rapidly, performing many computational steps within a single high-level cycle. It handles the fast, detailed computations and subordinate processing required to execute the sub-tasks defined by the H-module.

This can be understood through an analogy of a chess grandmaster working with a tactical analyst.[1] The grandmaster (the H-module) doesn't calculate every possible move. Instead, they form a high-level strategic plan, such as "control the center of the board." The tactical analyst (the L-module) then takes this abstract goal and rapidly calculates the concrete, specific move sequences needed to achieve it. Once those calculations are complete and a local objective is met, the analyst reports back. The grandmaster then re-evaluates the new, overall board state and issues the next strategic directive. This collaborative, multi-timescale process allows for both deep strategic planning and rapid tactical execution.

The Engine of Thought: Deconstructing HRM's Mechanics

The brain-inspired architecture of HRM is enabled by a set of novel mechanics that allow it to achieve deep, stable, and efficient reasoning. These mechanisms solve long-standing problems that have historically limited the power of recurrent neural networks.

Hierarchical Convergence: The "Reset" Mechanism

A common failure mode for standard Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) is "premature convergence".[1] As the network iterates, its hidden state tends to settle toward a fixed point too quickly. When this happens, the magnitude of the updates shrinks toward zero, effectively stalling computation and capping the network's effective depth.[1]

HRM overcomes this with an elegant process termed "hierarchical convergence".[1] Within each high-level cycle, the fast-updating L-module is allowed to converge to a local equilibrium—effectively solving one piece of the larger puzzle. However, this equilibrium is dependent on the context provided by the slow-updating H-module. At the end of the cycle, the H-module integrates the result from the L-module and performs its own update. This update establishes a fresh context for the L-module, which essentially "resets" its computational path and kicks it out of its previous equilibrium. It then begins a new phase of rapid computation toward a different local equilibrium.[1]

This process is visualized in the model's internal activity. The computational activity (forward residual) of a standard RNN rapidly decays to zero. In contrast, the L-module of HRM exhibits repeated spikes of activity as it converges within a cycle and is then reset by the H-module, which itself shows a steady, long-term convergence over many cycles.[1] This allows HRM to perform a long sequence of distinct, stable, nested computations, achieving an effective computational depth far beyond that of standard recurrent models.

Training with a Constant Memory Footprint

The primary reason recurrent models have been difficult to train for deep computations is the reliance on Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT). BPTT requires storing the entire history of hidden states from the forward pass to compute gradients, leading to a memory cost that scales linearly with the number of timesteps ($O(T)$).[1] This memory burden is often prohibitive, forcing compromises that limit the model's effective depth.

HRM introduces a breakthrough solution: a "one-step gradient approximation".[1] Theoretically grounded in the mathematics of Deep Equilibrium Models (DEQ), this method bypasses BPTT entirely. It computes gradients by backpropagating only through the final state of each module at the end of its respective cycle, treating all other intermediate states as constants. This reduces the memory requirement for backpropagation to $O(1)$—a constant footprint, regardless of the reasoning depth.[1] This powerful decoupling of computational depth from training cost is what makes it feasible to train HRM on the long, complex reasoning processes required for intractable problems.

Thinking, Fast and Slow: Adaptive Computation Time (ACT)

Inspired by the dual-process theory of human cognition ("System 1" for fast, automatic thinking and "System 2" for slow, deliberate reasoning), HRM incorporates an adaptive halting mechanism.[1] This system, called Adaptive Computation Time (ACT), uses a Q-learning algorithm to dynamically decide how much computational effort to allocate to a given problem.

At the end of each multi-segment forward pass, a Q-head predicts the value of two actions: "halt" and "continue".[1] If the problem appears solved, the model halts and returns the answer. If the problem is more complex, the model chooses to continue, initiating another segment of computation to further refine its solution. This allows HRM to solve simple problems quickly while dedicating more "thought" to harder instances, achieving performance comparable to a fixed-compute model while using substantially fewer computational resources on average.[1]

From Theory to Dominance: HRM's Performance on Intractable Problems

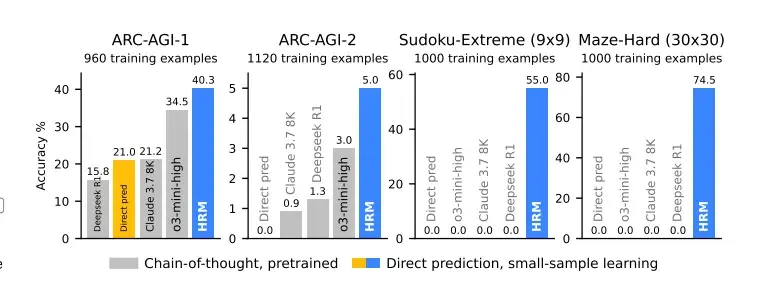

While HRM's architecture is theoretically elegant, its true power is demonstrated by its empirical performance. On benchmarks designed to test the limits of algorithmic reasoning, HRM achieves results that are not just incrementally better, but represent a qualitative leap in capability. It does this with only 27 million parameters and after being trained from scratch on just 1,000 examples per task, without any pre-training or CoT data.[1]

Solving the Unsolvable: Sudoku and Mazes

The most striking demonstration of HRM's power comes from its performance on tasks that demand extensive, deep reasoning traces, such as search and backtracking. On the Sudoku-Extreme benchmark, a dataset of exceptionally difficult 9x9 Sudoku puzzles, HRM achieves near-perfect accuracy. Similarly, on Maze-Hard, which involves finding the optimal path in complex 30x30 mazes, HRM again solves the task almost perfectly.[1]

What makes these results so revolutionary is the performance of the world's most advanced LLMs on the same tasks. When prompted using state-of-the-art CoT methods, models like Claude 3.7 and Deepseek R1 score a literal 0% accuracy.[1] They fail completely. This is not a matter of degree; it is a fundamental difference in capability. These tasks are simply intractable for models built on a shallow architecture that relies on linguistic reasoning.

Cracking the AGI Benchmark: ARC

The Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC) is a benchmark designed to measure general fluid intelligence through novel, IQ-test-like puzzles.[1] Success on ARC requires the ability to generalize abstract rules from just a few examples. On this challenging benchmark, HRM, trained from scratch, achieves a score of 40.3% on ARC-AGI-1. This substantially surpasses leading CoT-based models like 03-mini-high (34.5%) and Claude 3.7 (21.2%), despite their vastly larger parameter counts and context windows.[1]

The following table starkly illustrates the performance gap and highlights the power of architecture over scale.

| Model | ARC-AGI-1 Accuracy (%) | Sudoku-Extreme Accuracy (%) | Maze-Hard Accuracy (%) | Model Size | Training Samples | Pre-trained / CoT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRM | 40.3 | ~100 | ~100 | 27M | ~1000 | No / No |

| Claude 3.7 8K | 21.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Billions+ | Trillions+ | Yes / Yes |

| Deepseek R1 | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | Billions+ | Trillions+ | Yes / Yes |

| 03-mini-high | 34.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Billions+ | Trillions+ | Yes / Yes |

| Direct pred (8-layer Transformer) | ~16-20 (implied) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 27M | ~1000 | No / No |

Performance data sourced from the research paper.[1]

The "Direct pred" baseline, a standard Transformer with the same size and training data as HRM, also fails completely on Sudoku and Mazes, isolating HRM's hierarchical framework as the key driver of its success.[1] The evidence is unequivocal: for a certain class of intractable reasoning problems, a superior architecture is profoundly more effective than near-limitless scale.

Inside the Mind of the Machine: Visualizing HRM's Reasoning Process

Beyond raw performance metrics, visualizations of HRM's intermediate predictions offer a fascinating glimpse into how the model "thinks".[1] By observing the evolution of its solutions over time, it is possible to infer the underlying algorithms it has learned to solve these complex tasks. This analysis reveals a remarkable degree of cognitive flexibility.

An Adaptive Reasoner

The key takeaway from these visualizations is that HRM does not use a single, fixed algorithm. It autonomously discovers and applies different, task-appropriate reasoning strategies, a hallmark of general intelligence.[1]

- Maze Solving: Parallel Exploration and Pruning: When solving a maze, HRM does not simply follow one path. Its intermediate steps show that it initially appears to explore multiple potential paths simultaneously. Over subsequent timesteps, it progressively prunes routes that are blocked or inefficient, refining its solution until only the single, optimal path remains.[1]

- Sudoku: Depth-First Search and Backtracking: For Sudoku, the model's process strongly resembles a classic depth-first search algorithm. Visualizations show it filling in numbers based on the current board state. When it reaches a contradiction—a cell that violates Sudoku's constraints—it appears to backtrack, erasing its recent moves and trying a different possibility.[1] This ability to explore and backtrack is crucial for solving hard logic puzzles and is something standard feed-forward models cannot do.

- ARC: Iterative Refinement (Hill-Climbing): On ARC tasks, HRM employs yet another strategy. Instead of the deep search seen in Sudoku, its solution path follows a more consistent progression. It makes a series of small, incremental adjustments to the input grid, iteratively improving the board state until it matches the target output. This process is analogous to a hill-climbing optimization algorithm.[1]

The fact that HRM autonomously discovers these classic, human-understandable algorithms simply from being shown input-output examples is profound. The structure of the problems themselves guided the model, via gradient descent, to learn optimal computational procedures. This suggests that the model is not just memorizing patterns but is learning fundamental principles of computation, a critical step toward more general and interpretable AI.

A Bridge to Biology: Emergent Brain-Like Organization in a Neural Network

Perhaps the most scientifically significant finding related to HRM is not just its performance, but the deep structural parallels that emerge between its internal organization and that of the mammalian brain.[1] This connection moves beyond inspirational analogy to a quantitative, measurable similarity, suggesting a form of "convergent evolution" for intelligent computation.

The Shape of Thought: Dimensionality in the Brain

A key principle in systems neuroscience is that a brain region's functional complexity is linked to the dimensionality of its neural representations.[1] This "effective dimensionality" can be measured using a metric called the Participation Ratio (PR). A high PR indicates that information is distributed across many dimensions, allowing for flexible, context-dependent representations. A low PR indicates that information is concentrated in a few dimensions, suitable for more specialized, constrained computation.[1]

Studies of the mouse cortex have revealed a clear dimensionality hierarchy: higher-order, abstract reasoning areas like the prefrontal cortex exhibit high-dimensional activity, while lower-level sensory and motor areas exhibit lower-dimensional activity.[1] This organization is believed to be fundamental to how the brain supports complex cognitive tasks.

An Emergent Hierarchy in Silicon

Remarkably, after being trained to solve reasoning problems, HRM's modules spontaneously organize themselves into the very same hierarchy.[1] Measurements show that the high-level (H) module develops a high-dimensional representation (PR of 89.95), while the low-level (L) module operates in a much lower-dimensional space (PR of 30.22). The ratio between these dimensionalities in HRM ($z_H/z_L \approx 2.98$) is strikingly close to that observed in the mouse cortex ($\approx 2.25$).[1]

Crucially, a control experiment with an identical but untrained HRM showed no such hierarchy; the PR values of its modules were low and nearly indistinguishable.[1] This proves that the brain-like dimensionality hierarchy is not an artifact of the architecture itself but is an emergent property of learning to reason.

Both evolution and gradient descent, when faced with the problem of optimizing a system for complex, goal-directed behavior, independently discovered the same structural solution: separate a high-dimensional, flexible "planning" space from a low-dimensional, efficient "execution" space. This finding provides some of the strongest evidence to date that the organizational principles of the brain are not biological quirks but are fundamental, and perhaps universal, principles of efficient computation.

Conclusion: A New Trajectory Towards Universal Computation

The Hierarchical Reasoning Model is more than just another novel architecture. It represents a direct challenge to the dominant paradigm in artificial intelligence and offers a compelling new trajectory toward the goal of universal computation. By demonstrating that a small, principled, brain-inspired model can decisively outperform massive, state-of-the-art LLMs on a class of intractable reasoning problems, HRM forces a re-evaluation of the belief that scale is the primary driver of progress.

The model's success is built on a foundation of key innovations. Its hierarchical and multi-timescale structure allows for the separation of slow, deliberate planning from fast, detailed execution. The elegant mechanics of hierarchical convergence and the one-step gradient approximation solve the historical training bottlenecks of recurrent networks, finally decoupling computational depth from training cost. This breakthrough moves the theoretical promise of Turing-complete recurrent models much closer to practical reality, enabling them to execute the long and complex algorithms that true reasoning requires.[1]

Ultimately, HRM suggests that the future of AI may not lie in ever-larger, monolithic models but in more structured, heterogeneous systems that emulate the functional organization of the brain. Its success validates a more science-driven approach to AI—one focused on discovering and implementing the fundamental computational primitives of intelligence. The Hierarchical Reasoning Model is not just a better reasoner; it is a foundational step toward a new class of general-purpose AI systems capable of truly thinking.